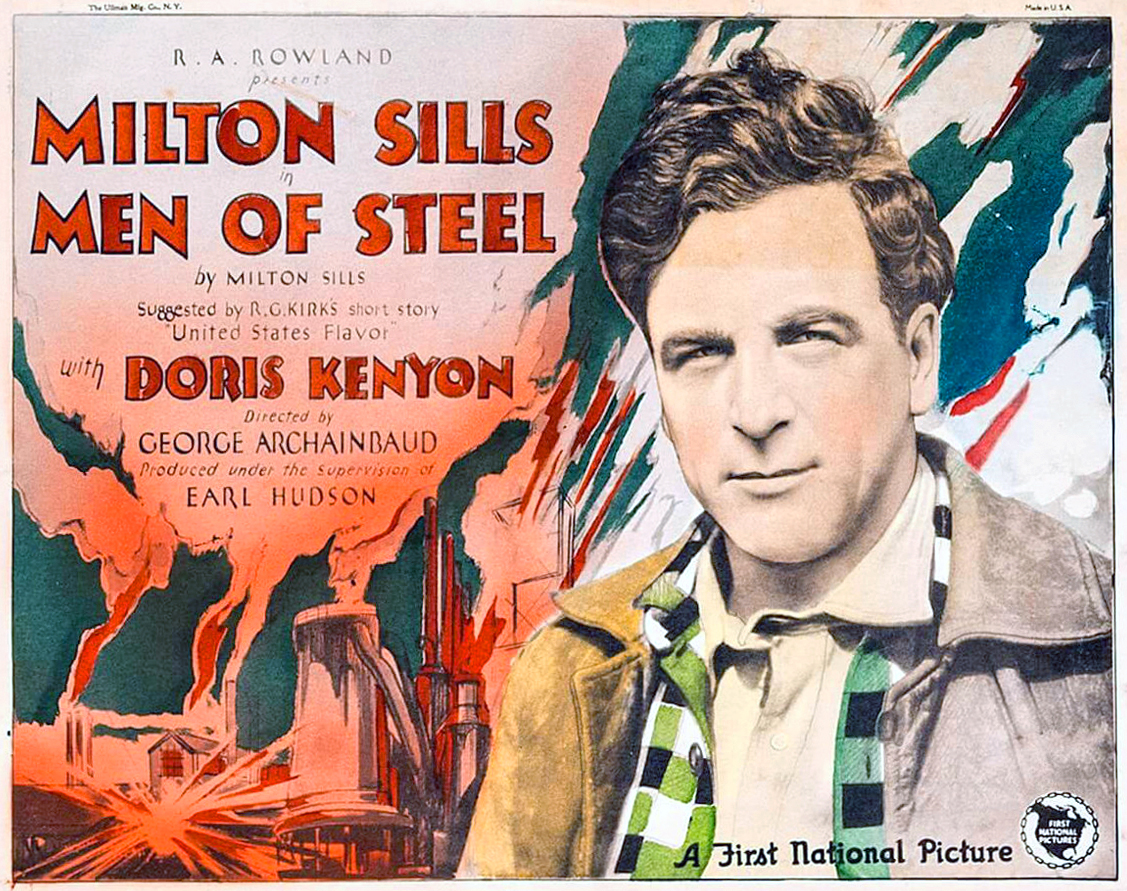

Milton Sills was a huge star of the silent era. His name and face may be unfamiliar today but he would have been an ideal “get” for Encyclopedia Brittanica to write about screen acting techniques for its 14th edition, published in 1929. And not a moment too soon – talking pictures were about to change everything, and Sills himself passed away unexpectedly in 1930.

In a brief section whose sub-head is Future Possibilities, Sills ruminates on what the talking picture might entail as far as performance techniques. Given the speculative nature of how he was writing about talkies, it’s possible his piece was written in 1928. But he’d been a leading man in feature-length pictures since the late 1910s after having one of the leads in the 1917 serial Patria starring Irene Castle.

So, he had a ton of experience under his belt to back up what he laid down on paper at what turned out to be the end of the silent film era. The article is several pages long, covering many different aspects of production, actor’s techniques and how they relate to one another. But halfway down the right hand column on page 891, Milton Sills spelled out in black and white what I’d been seeing in my deconstructions of silent film segments, as far as taking speeds, projection speeds and the way performers were compensating for this.

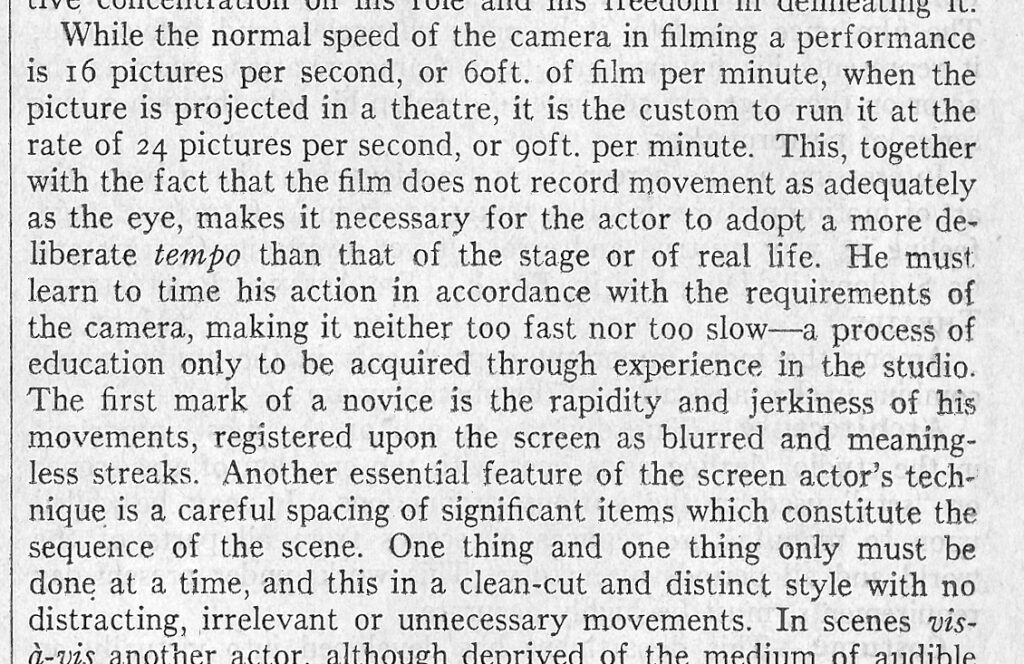

While the normal speed of the camera in filming a performance is 16 pictures per second, or 60 ft. of film per minute, when the picture is projected in a theatre, it is the custom to run it at the rate of 24 pictures per second, or 90 ft. per minute. This, together with the fact that the film does not record movement as adequately as the eye, makes it necessary for the actor to adopt a more deliberate tempo than that of the stage or of real life. He must learn to time his action in accordance with the requirements of the camera, making it neither too fast nor too slow – a process of education only to be acquired through experience in the studio. The first mark of a novice is the rapidity and jerkiness of his movements, registered upon the screen as blurred and meaningless streaks. Another essential feature of the screen actor’s technique is a careful spacing of significant items which constitute the sequence of the scene. One thing and one thing only must be done at a time, and this in a clean-cut and distinct style with no distracting, irrelevant or unnecessary movements.

Encyclopedia Brittanica (edition publ. 1929), “Motion Picture Acting”, p. 861.

The feet per minute numbers are a bit of an oversimplification. Different scenes or shots could be and were (to my eye) taken at a variety of speeds, depending on the action or mood. 18 fps or even 20 fps was pretty typical by 1928. Projection speeds were also not regulated or locked down. Research I’ve done has found that by 1926 or 1927, 100 feet per minute (or approximately 27 fps) was a typical running speed. Faster in some of the smaller houses.

Typical projection speeds had started out in the early-to-mid ‘teens at 16-18 fps (and cranking speeds slower than that), and had been gradually creeping up over the ensuing 8-10 years. More details on that will follow in a future post.

But still, Milton Sills declaration in the Encyclopedia about How This Works confirms what Maurice Costello had discovered at the end of the nickelodeon era when he entered moving pictures: that they were taken at one speed and presented at a faster one. And, more importantly – and this is the smoking gun, trade-secret sleight-of-hand part – that performers were compensating for this by adjusting the way they were moving.

This performance technique is precisely what makes Silent Film look the way it does. We’ve all missed this, for decades, and this is what I discovered in scrutinizing the step-printed footage from Chaplin’s A Dog’s Life. That, from a certain point in the early ‘teens, Silent Film should be projected faster than taking speed, because the people who made them were expecting this and built this awareness into making the films so they’d look “right” for audiences.

The first post in this series is here.

The previous post (#49) to this one is here.

The next post (#51) to this one is here.