For a clown, a real honest-to-goodness Clown, the core of what they are doing is rooted in the honest, raw, vulnerable connection they create and have with the audience members. This is the source of where the laughs come from. The costuming and make-up are an extension or exaggeration of who the clown performer is, inside, and which resonate with the audience. What most people associate with clowns is just what’s on the surface – the red nose, the make-up, hat and shoes, etc. – but it’s this human connection during the show itself that’s what clown really is.

It is precisely this connection which all clowns strive to develop and achieve that may be why circus clowns never quite made it in silent film.

The instant you put a camera between the live performance of a clown and the audience, that connection goes out the window and all that’s left is the mechanics of the clown’s performance, in their face and body. There’s a huge difference between going to the circus and watching a video of one of that circus’ clown’s performance on YouTube.

The “Clowning Around (the World)” program in the Silent Comedy International series at MoMA – which I’m co-curator on – takes a look at some examples of attempts at making this work.

The clown Toto was hired by Hal Roach to make short films in the late ‘teens. He was apparently difficult to work with and, the story goes, his discomfort with working with water was exploited to get to him to quit. Toto may have had a hard time working in the context of what was essentially wordless sketch comedy. A clown can come out on stage with a chair and a prop or two and work for 8-to10 minutes, and his or her laughs come from that connection to the audience, and not as much from the business they’re doing. It’s a real stretch, especially if you’ve got to create, shoot and release a 12-minute plot-based wordless comedy film in a week. Fortunately some of the physicality and physical comedy routines Toto developed are preserved on film, and you can see them in His Busy Day (1918). There’s some typical “park comedy” in the first half, and in the second half Toto is at work at a newsreel company’s office — and manages to shoehorn in what appears to be a clown routine with a tilting/rotating sign.

Harry Watson, Jr. had better luck adapting to movies, although it was short-lived. The serialized Mishaps of Musty Suffer found him teamed with director Louis Myll in three ten-film series of episodes (listed onscreen as “whirls”) that were made and released in 1916-1917. Watson and clown partner George Bickel had been Ringling clowns in the 1890s and were in that circus’s first clown band. In the early 1910s they were headliners in the Ziegfeld Follies, where their Little German Band and boxing routines were put to use. The Musty Suffer comedies were a unique and bizarro blend of Watson’s clown tramp character and Myll’s surreal sets and set-pieces that somehow anticipate Dada without ever having been in contact with it. Outs And Ins (1916) finds Musty at work in an automat and, like the other “whirls” feels like a combination of early French trick films and cartoons that Bob Clampett directed in the late 1930s at Warner Brothers. When the Musty series ended, Watson went back to the stage.

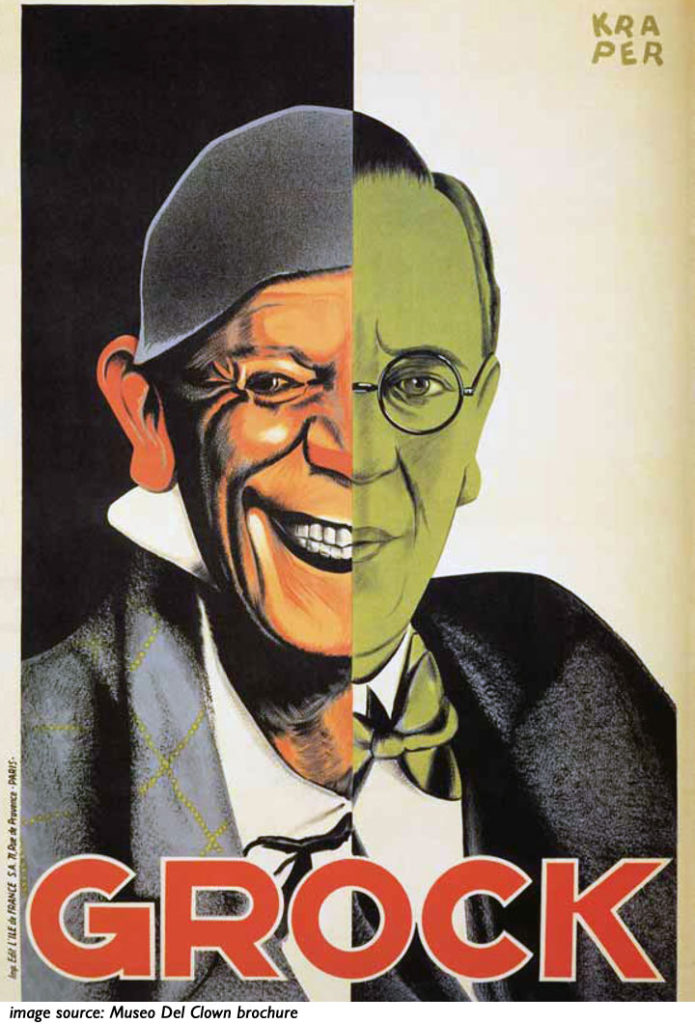

The clown known throughout Europe as “Grock” only made two films, the Son Premier Film (1926) and the eponymous Grock (1931). The latter is primarily a performance film, and hunks of it are easily findable on YouTube. The silent “His First Film”, while uneven, is an attempt at placing Grock (Karl Adrien Wettach) in a vehicle whose storyline and plot leave room for him to perform or to interpolate physical business into the scenes here and there. It’s very well-made, there are a few Chaplinesque moments of pathos, and a number of deus ex machina plot maneuvers that propel Grock through the thin storyline.

Son Premier Film was restored by the Centre national ducinéma et de l’image animée (CNC) in 2010. Once Steve Massa, Dave Kehr (MoMA) and I chose the theme for our series, this film leapt to the top of my list, so that it could be seen by classic film fans and circus folk alike. The production values are good, and we get a glimpse at the films studios of Albatros, and while there are “you really had to be there” aspects of the film that assume we know and love Grock that are lost to time, you do get to see the man up close doing his thing.

The program “Clowning Around (the World)” screens Sun Nov 25 and Thurs Nov 29 with live musical accompaniment in the Silent Comedy International series at MoMA.

Sequences from the performance film Grock are on YouTube here. For more about clowns and what they’re about, pick up a copy of David Carlyon’s The Education of a Circus Clown or John Towsen’s book Clowns (way out-of-print…you may need to find it in your local library) or his physical comedy blog All Fall Down. And if you’re ever in Italy, visit the Museo del Clown, in the Villa Grock, whose website will fill you in even more on the “King of Clowns”.