You don’t see a lot of detective stories in silent cinema. Almost as remarkable as the rediscoveries of silent Sherlock Holmes films is the fact that very few were made at all. The Language of Silent Film doesn’t lend itself to detective stories all that well, which is why you see more of Junior than Holmes in any Sherlock-type silent.

One of the floodgates that talking pictures opened was the ability to tell detective stories. There is so much exposition and intrigue to be conveyed in any detective story, including the private eye’s discussing his suspicions and theories about the evidence and the trail they’re on. This would, of necessity, have to reside in intertitles (referred to in the 20s as “sub-titles”). This would, of course, bog down any physical action and dramatic movement of the story.

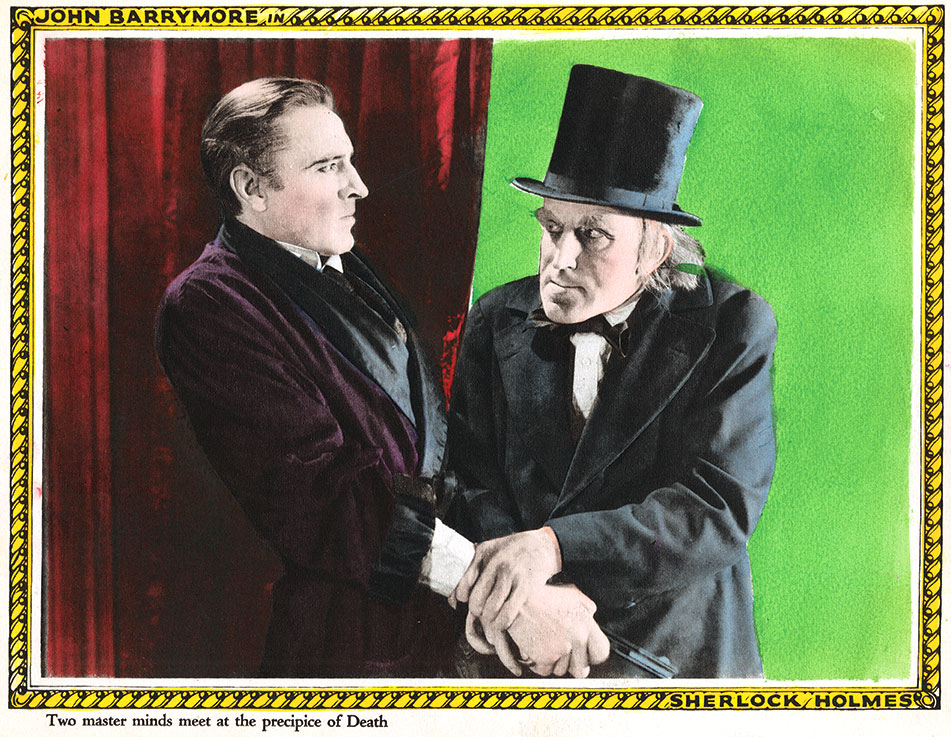

The Sherlock Holmes films with William Gillette and John Barrymore demonstrate this. Silent film is a tough medium to employ for the genre, which is ironic, considering the many inventive ways that characters’ internal narrative and reactions are realized onscreen in silent film. The trick is that with a detective story, so much of that internal narrative is left-brain, fact and fact-connecting machinations. Thought processes that, even with the male and female actors in silents whose thoughts you can read in their faces, can not be conveyed.

There are certainly characters in silent films who are introduced to us as detectives an supporting or ancillary characters, but they’re rarely the main protagonists or drivers of the story.

Except in comedy films.

In silent comedy films, there are little if any complicated theories and plot machinations to be followed. For Sherlock, Jr. (Keaton), Coke Ennyday, (Fairbanks) or Max Asher and Gale Henry in The Adventures of Lady Baffles and Detective Duck, the emphasis is more on the following of the suspect and eventually chasing them while also rescuing the bad guy’s captive or stolen jewelry, or both. The title-bound exposition is more of the “Ah-hah…it’s that guy!” type of intrigue, and then our sleuth is off on the next bit of action.

It’s part of the fun and the secret to the Blake Edwards Pink Panther films, as well. They’re not really detective stories. They’re comedies where there is very little complicated plot twists. Mostly, the turns of story are Clouseau’s comedy set-pieces spurred on by mistaken information he’s picked up in the attempt to recover a stolen jewel. It’s not James Bond or Hercules Poirot with jokes.

Silent serials manage to succeed best with the genre, but they’re by nature action-based. And so we have a title or two letting us know that X suspects Y now, and off X goes in perilous pursuit of Y.

Despite the popularity of the detective-as-lead-character in printed fiction, pulp and regular, and on the stage, it would have to wait until all the initial singing and dancing of early talkies died down to quickly take hold as a film genre.