Buster Keaton, along with Larry Semon, made the best use of taking different shots at different cranking speeds within a scene. This part of the Silent Film language was available and used by everyone in the silent era. Since the film was running faster in projection, mixing cranking speeds is undetectable.

Action stars like Douglas Fairbanks or the Helens Holmes an Gibson of the serials did this as well, but this flexibility with speed — and consequently the laws of physics and gravity — allowed comedians a much broader gag spectrum than was possible on stage or in the circus ring.

I made and posted this undercranking study from a sequence in Buster Keaton’s Sherlock, Jr. (1924) several years ago for the lecture on undercranking that I do. I’d posted it on YouTube but it got removed for copyright reasons. Now that we’ve rung in the New Year and this film has entered the public domain, I’ve put the clip back on my YouTube channel.

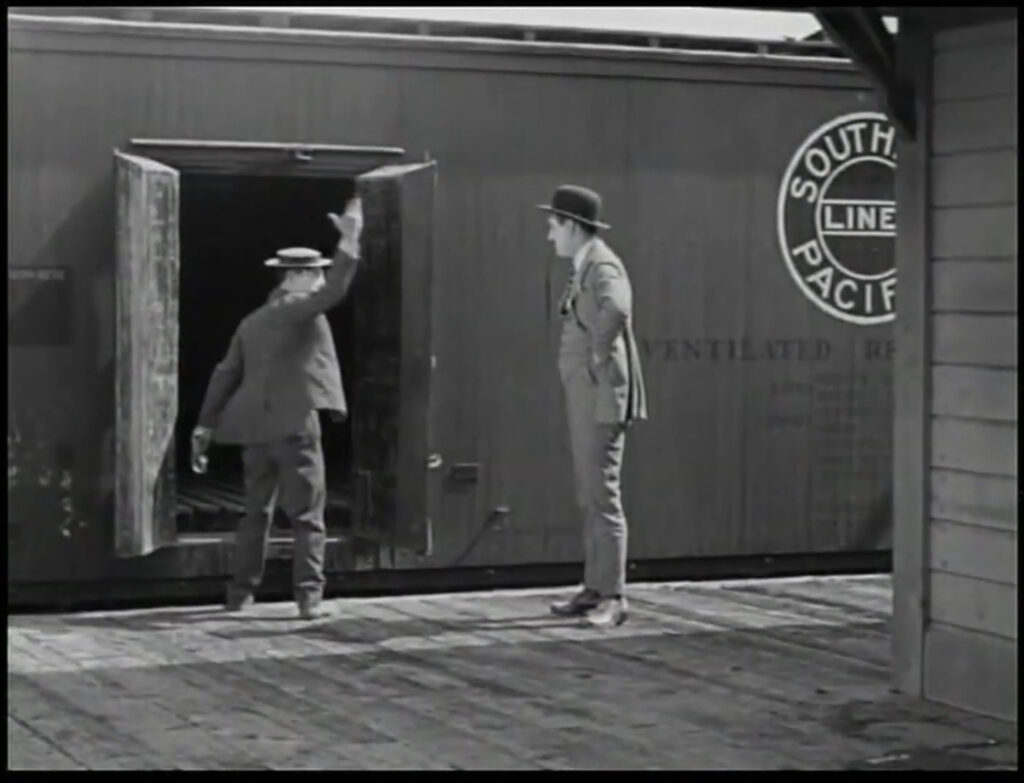

In the “trailing a suspect” sequence from Sherlock, Jr. you’ll see the careful choreography and timing of the tracking shot where Buster is literally two steps behind Ward Crane and where they avoid a passing automobile, and how Keaton (and Elgin Lessley) seamlessly shifts from cranking at 16 to cranking at 12 for the iconic sequence atop a moving locomotive.

In addition to the movement aspects of the comedy work seen here, the sequence demonstrates one of my favorite rules of silent film and silent film comedy: if the onscreen performers do not indicate that they hear something, that sound does not exist. In reality, and in a sound film, Crane would hear Keaton walking behind him. In a silent film, though, the logic of this is completely plausible.

Three things to note that I’ve noticed or found out in the years that have passed since I recorded the voice-over for this video:

- There’s a moment of time-elision, only possible with the speed-up of silent film, where Keaton catches Crane’s tossed cigarette and turns it around with a sleight-of-hand move so he can take a puff

- the hand-car that slides in at the end of the last shot is not a full hand-car but is instead just a chassis. This was caught and pointed out to me by the late James Cozart, film preservationist at the Library of Congress, after I gave my talk there during the annual Mostly Lost workshop, This makes complete sense, as the timing and work of getting a full hand-car up to speed and entering the shot at just the right moment would have been even more difficult.

- not everyone knows Buster Keaton broke his neck in that last shot, when the deluge of water slammed him into the rails. My comment “didn’t hurt him a bit” is meant as a joke, and I mistakenly assumed this bit of history was well-known. Someone posted a comment on the YouTube listing calling me out for not knowing this, since my comment also sounds like I had no idea. Which is valid. My bad. Gotta know your audience.

Enjoy!

NOTE: there are no shooting records for these films; my determining cranking speeds is based on research and by watching the individual shots at a variety of speeds paying close attention to things like body weight, dust and smoke, etc.

For more of my video studies on silent film comedians’ use of the speed-up of silent film, visit my YouTube channel for this subject.

My undercranking lecture was turned into a disc extra by the Criterion Collection, called A Study in Undercranking, which you can watch on their DVD/Blu-ray released of Chaplin’s The Kid, or on their streaming service.