The second time I play for a film is my first big chance to make improvements over what I did the first time. If my first bash at the picture was a show where I’d not been able to preview it, I can make more specific or bolder choices for the film’s beginning, to help set the tone. Occasionally this proves difficult.

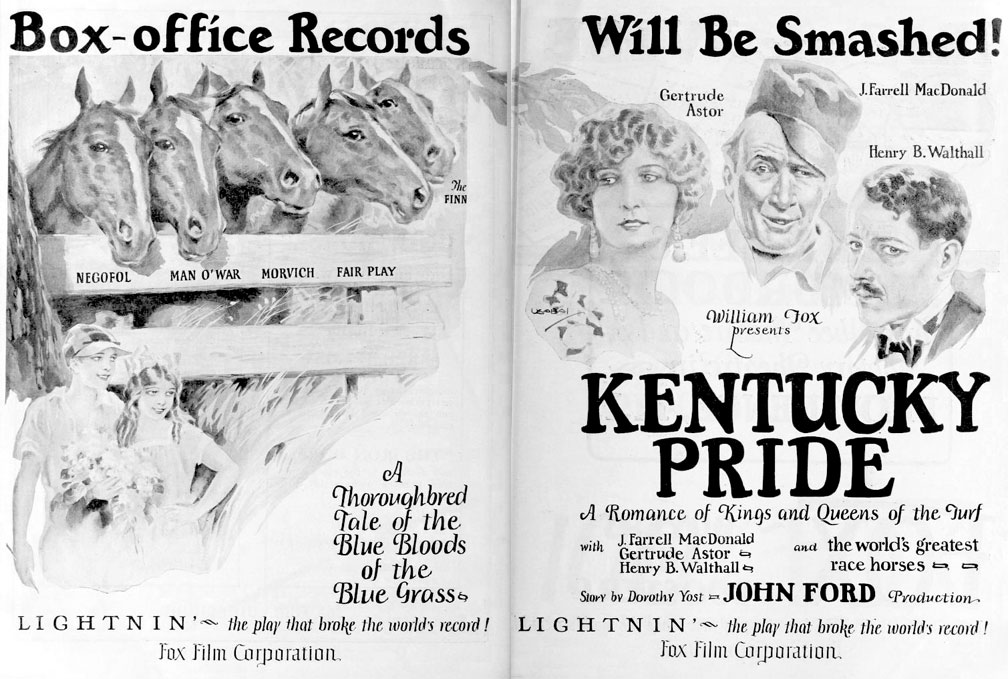

I want to help the audience dive into the world of the film. The music at the beginning of a film, during its expository scenes, support the onscreen information as to locale, era, style and genre. In some cases it’s a trickier entry. I know I was puzzled by how best to handle the beginning sequences of Kentucky Pride, the 1925 John Ford picture recently restored by MoMA, which will screen at Capitolfest this weekend with yours truly at the Möller theatre organ.

One of the aspects of the language of silent film I cover with my students at Wesleyan and which we discuss throughout the semester, is the way titles are used. How much information is given to us in the intertitles — referred to as “subtitles” during the silent era — and how much isn’t. Are we being spoon-fed information we don’t need to be told to us? Are we given just enough to help us decode the sequence?

I refer to playing for a film without having screened it in advance as “sight-reading” the film. It’s a term I’ve borrowed from music terminology, but it fits. Sometimes there isn’t time, sometimes there isn’t a screener video available. I don’t tell the audience, and they usually can’t tell. There’s a method to accompanying a film I’ve developed that makes this possible.

The opening sequence of Kentucky Pride shows us the lay of the land, figuratively and literally, showing us the countryside and the ranch where a horse has been born and raised. There are intertitles with information, and shots of the ranch, corral etc. This sequence resolves with a few shot-then-title bits where we are shown a medium-wide shot of a horse, then a title explaining something about our story.

It was at this point, during the show I was playing at MoMA in March, that I realized the titles were things the horse was telling us. There is no title card at the top of the film that shifts our viewpoint form third-person narrator to p.o.v. narrator that says “Who better to tell us about this than the horse?” The horse’s mouth doesn’t move, so we’re tasked with combining a shot of a horse with a dialog title and putting this together ourselves.

There are a couple places in the film, if memory serves, that the horse-as-narrator device disappears and reappears, that the whose internal narrative (or not) this is shifts gears. This is not a criticism or a dig, it’s something else my students and I discuss after viewing each film. It happens in lots of silents. It’s precisely because of the imaginative elasticity of the medium of Silent Film itself that we can be presented with this type of narrative fluidity and accept it.

But, is there a way to use music to help clue a contemporary audience in to the fact that our third-person narrator of the expository titles in Kentucky Pride is the horse? I don’t know that it’s possible to do that without some sort of elbows-out wink-wink anachronistic use of the theme from Mr. Ed. What I can do, and which I think I did during that show in March, is to establish the horse’s leitmotif during this and bring it back around when it happens again…making sure not to use it too many times so it doesn’t become obvious.

Subscribe to this blog below so you don’t miss a post! I hope you’ll consider joining my email list, or browsing through some of my recent posts (on the right or below). [email-subscribers-form id=”1″]