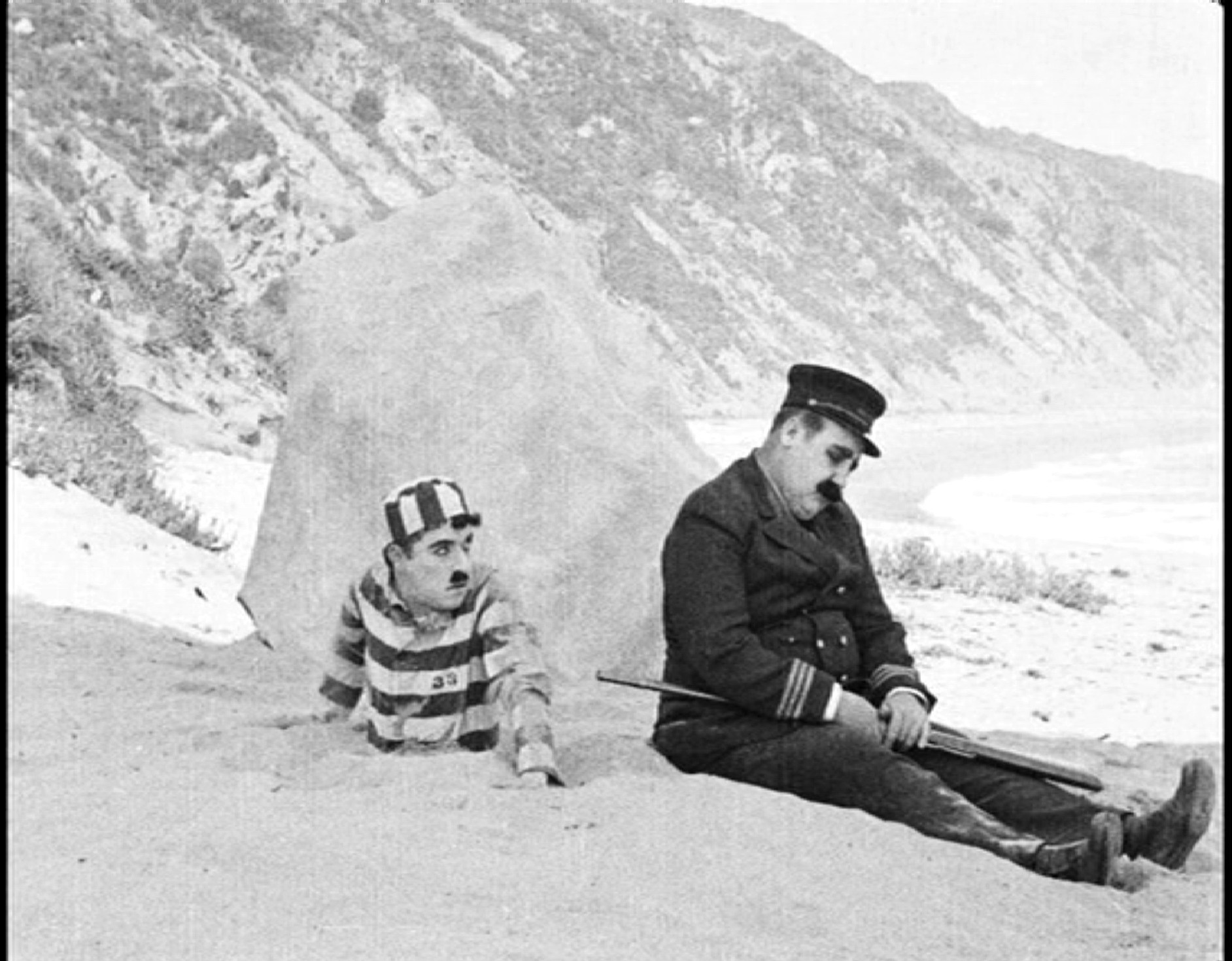

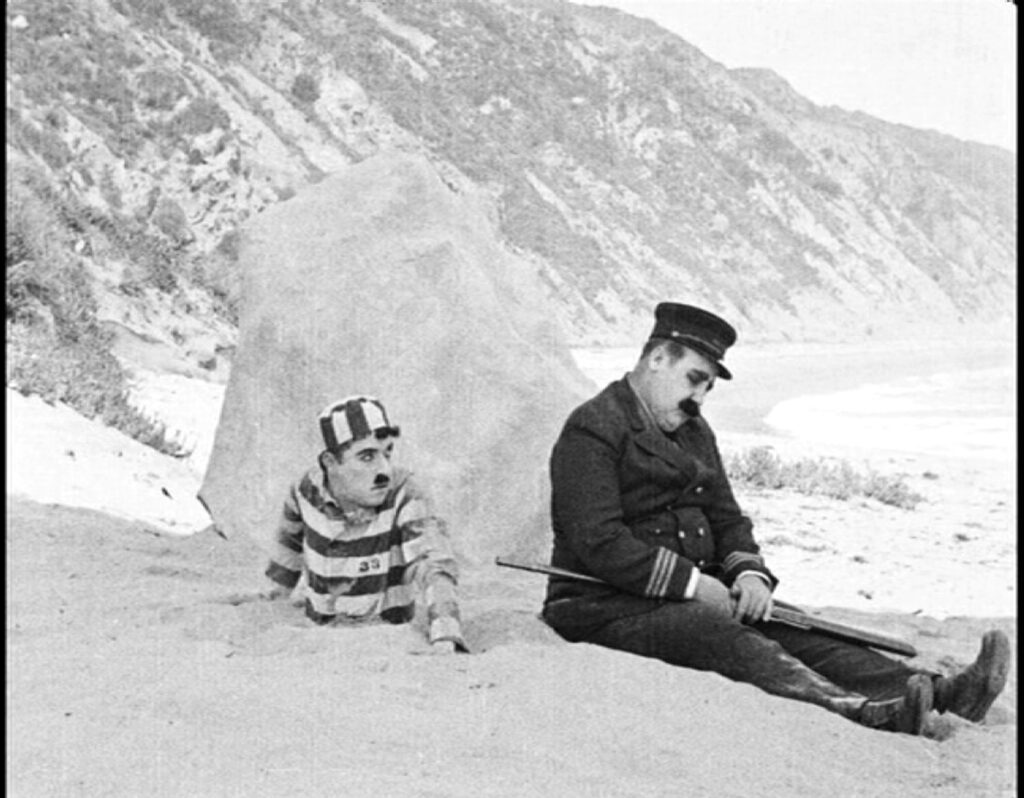

We know who on the train with us is a conductor by their uniform. When I see a film crew in my neighborhood, I know which of the people standing around drinking coffee is going to stop me from walking because they’re holding a walkie-talkie and because they’re in the middle of the sidewalk or on the corner. The story-book simplicity of the way we are fed information in Silent Film works the same way in its use of character archetypes.

We don’t have the capability to listen to a conversation between two people in which one of them mentions being out on her yacht over the weekend to figure out she’s wealthy. We also don’t have the time for it. Sometimes a title can give us that clue but it’s much easier and less of an interruption for someone to be dressed a certain way and have just enough haughtiness in their physicality for us to figure this out.

The use of character archetypes is a visual shorthand for viewers so we know who everybody is, instantly, when we see them. So we can get right on to the business or story point or gag set-up and keep things moving along. We pick up these clues, even from people who are not wearing a uniform. Granted, one may need a certain amount of knowledge of the culture of the time when watching a silent movie from the 1910s or 1920s, but the costuming iconography is still there to indicate quickly know who’s who.

It’s like opening your front door on Halloween and seeing a bunch of kids in different costumes. You know who’s dressed as what. (Well, most of the time.)

I’m not exactly sure how or when this became part of the storytelling lexicon. It obviously comes from stage traditions, but what’s interesting is that the practice takes hold as a visual shorthand early on and is maintained throughout the rest of the silent era. It doesn’t completely disappear when sound comes in, of course, but is no longer the key identifier as to who someone is or what their occupation or background or class is, because we now have all that conversation to tell us.

With Silent Film, we’re shown a big hint, and even without a lot of detail we take the hint and that’s usually enough. We don’t necessarily fill in a lot of detail with our imaginations but there’s not a need for that.

The first post in this series is here.

The previous post (#33) to this one is here.

The next post (35) is here.