There was something slightly unsettling about the employment office sequence I saw in the “The Chaplin Revue” (1959) of “A Dog’s Life”. It wasn’t just that it felt like it was running too slow. An easy call to make but difficult to explain. I wanted to know what the explanation was. Years after seeing this in a revival house I figured out why it seemed to be running slower than it should be.

(BTW, I’d dropped the ball on this thread back in May, and am picking it back up now. If you want to read the post that sets this post up, read it here…but do come back.)

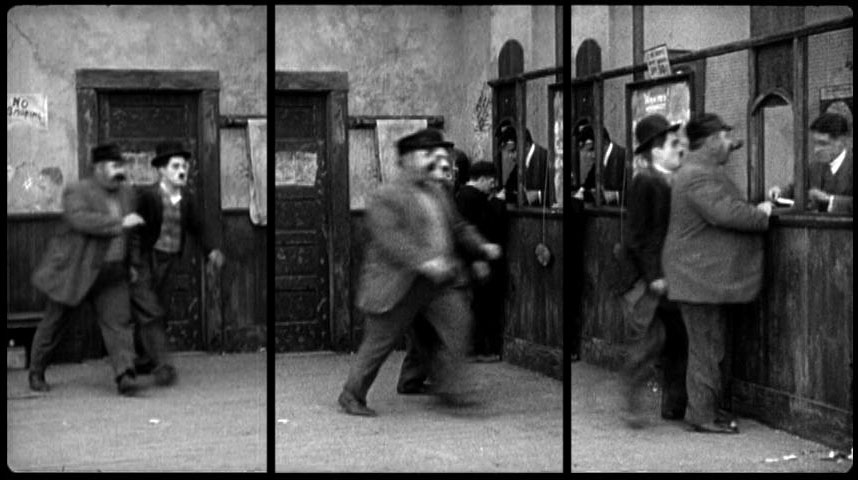

I got my hands on a DVD of The Chaplin Revue and took a look at the sequence in question, the one where Chaplin kept going up to the window and everyone else kept getting in front of him. I vaguely remember that I’d somehow ripped the file and brought into iMovie (that’s how long ago this was), and sped the footage up a little.

And…bingo.

Not only did the sequence “look right”, but two things were now in place. The business was funny, and I was now seeing the Charlie Chaplin I knew. Rather than seemingly and stupidly letting each of the other men slip in front of him over and over, what I now saw was the Little Tramp earnestly walking briskly to the window and each time someone zipped in front of him at the last instant and snagging the job offered at the window. This was then capped by the clown business of his being caught up in the routine of dashing back and forth, repeating the action even after there were no jobs left and no more men running up to the window.

How did this happen? How was this suddenly a Charlie Chaplin physical comedy routine where moments before it, well…wasn’t.

This was my big light-bulb-over-the-head moment, when I realized that silent film wasn’t just the slightly-faster projection speed, but that it was a combination — really a collaboration — of performance and that speed-up. Of knowing the film would be shown faster in theaters and utilizing the speed-up by moving or creating movement at a different and specific pace for it.

The very reason that Silent Film does not look merely look the way film does when it’s run faster. More on this, in my next post…

The first post in this series is here.

The previous post (#45) to this one is here.

The next post (#47) to this one is here.