I’ve scored a few films over the past year-and-a-half for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Spirals”, a 2½ minute “art film” made for the Met in 1970 by Joyce Chopra, is the first one I’ve done for the museum that was not a silent movie, per se. But I drew on my accompaniments to other non-linear or Dada silents for musical inspiration.

These films are freeing, creatively, in that expectations of what you can play or would-or-should be hearing reach more into less-traditional melody. I’ve found a balance between conventional melody and blatant dissonance for these, inspired by music by composers like Satie, Stravinsky, Shostakovich (why they’re all “S” composers I don’t know) and the piano compositions by Bix Biederbecke (In a Mist, Candlelights, et al).

Getting to accompany experimental, impressionistic or less-linear silent films have been oportunities to stretch what I can get away with musically. 1920s films likeThe Bridge, H20, The Seashell and the Clergyman or The Life and Death of 9413, a Hollywood Extra (1928). Same for the travelogue-like polar exploration films I’ve played for at the Stumfilmdager (“Silent Film Days”) festival in Tromsø, Norway. They don’t visually utilize standard linear narrative, leaving a little more room to use a more expanded musical palette.

My first idea, when I watched the screener for Spirals (1970), the first sound I heard in my head, was 1970s analog synthesizers. Turned out I wasn’t far off, as the music originally used with the film was from the Wendy Carlos album Switched On Bach (Columbia, 1968). If you watch it with the sound off, without what I came up with, you’ll probably hear that in your head as well.

I connected one of M-Audio 61-note keyboard/controllers to my MacBook and hit a wall with working with the samples. Not a wall as much as a series of tiny tech hurdles, and as much as I figured I could work these all out, I also sensed myself going down a trouble-shooting rabbit-hole that was going to get in the way of creating any music.

I reverted to the Steinway D digital samples I usually use, and began watching the film. I’m not sure why, but I almost immediately heard or felt a meter and tempo, and started messing with an arpeggiated riff underneath the film’s opening.

- meter – number of beats in a bar of music; in this case it was three-quarter time, or what you’d think of as a waltz.1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2-3 except that…

- tempo – means speed, and in this case my instinct was running at a brisker-than-waltz speed for the…

- arpeggiated riff — “arpeggiated” means taking a chord of 3 or 4 (or 5) notes and instead of playing them at the same time, playing the notes one at a time, in a sequence.

I began building the musical phrase that went under the first section of the film, playing and repeating phrases in different keys or pitches.

What developed as I recorded or sequenced the notes and bars of music was fascinating. The tempo and feel of the music I was creating seemed to fit the editing structure. As a filmmaker myself, when I look at a sequence like this that has no apparent structure, I know that that’s not the case. Nobody just arbitrarily splices a bunch of shots together and calls it a day. I always assume there’s an internal logic to the editing and try to understand it, so I can better support it musically.

I dealt with this in a big way when I scored Ernst Lubitsch’s So This is Paris (1926) for Turner Classic Movies last year. The film’s infamous Charleston sequence lasts about 3 mins, during which absolutely nothing happens in terms of the film’s story. It’s 3 minutes of footage of a large crowd of people dancing. In a silent movie. No cutaways to something involving the plot, just shots of a big Charleston contest. Rather than just jam for 3 minutes, I watched the sequence over and over until I was able to find the internal editing structure of the piece, and saw where sections of it began and ended.

I wasn’t able to spot these as readily while scoring Spirals, but I kept noticing that as an 8-bar or 10-bar musical phrase ended, another slightly different grouping of shots would begin. And so I created a new musical phrase for it, or “borrowed” one from earlier in the film, the way a song might have a chorus or verse or bridge.

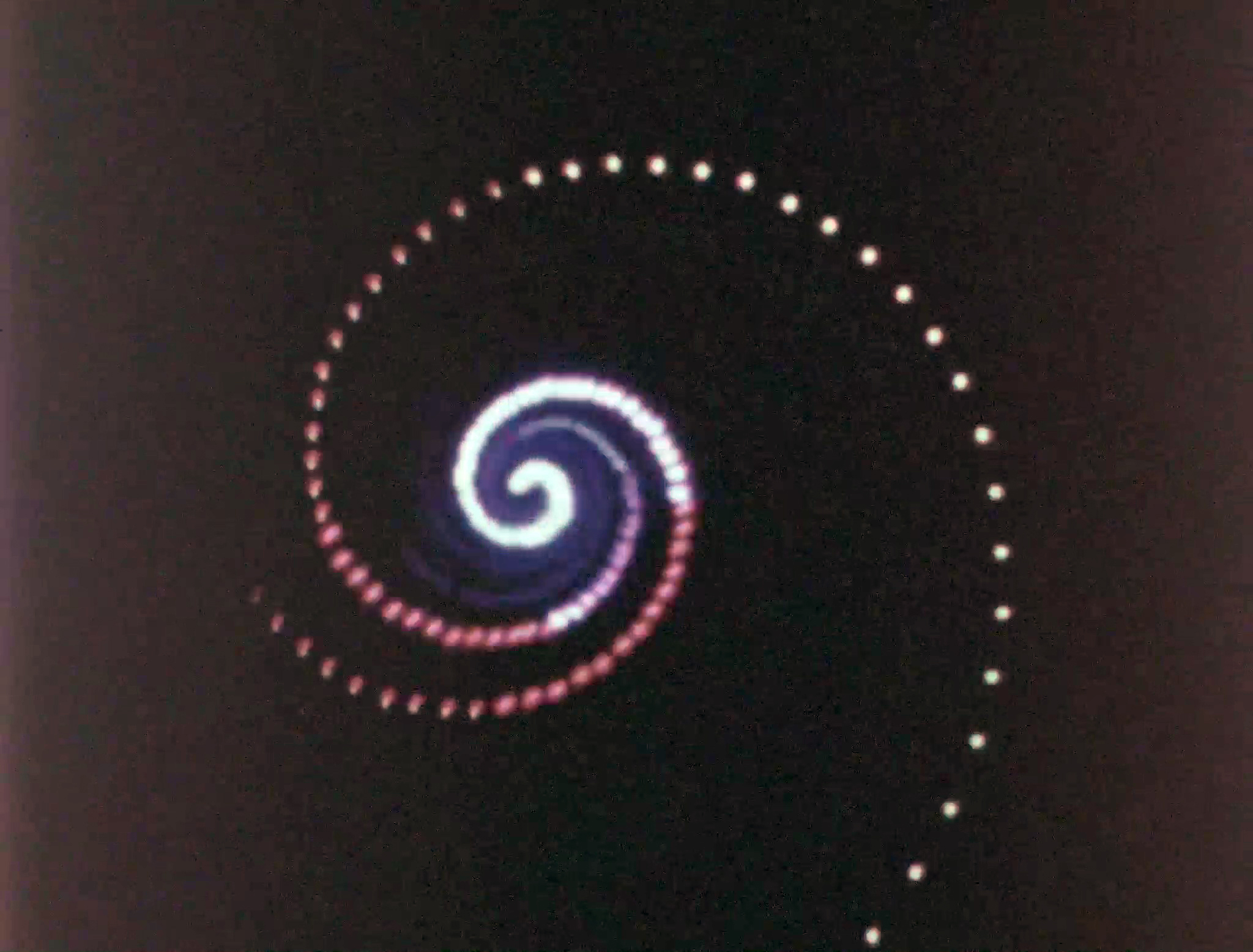

In the end, even thought I wound up scoring the film on piano, I think what I wound up creating fits the film organically. It keeps it moving ahead, ebbing and flowing in its energy and visuals. It makes the film something more than the abstract gathering of footage of different examples of spiral designs in nature and human activity it could seem to be on the surface. I’m quite sure filmmaker Joyce Chopra put a lot of time, work and thought into making Spirals for the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Read a New York Times article from August 1971 about the “Eye Opener” exhibit for which the Spirals film was made, here. The exhibit was a year-round mobile art show that traveled by trailer and visited NYC hospitals, and was sponsored by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the city’s Depart ment of Cultural Affairs.

Here’s the film, embedded from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s From the Vault site, which showcases holdings from the Met’s film collection. You can view the entire collection of posts here.