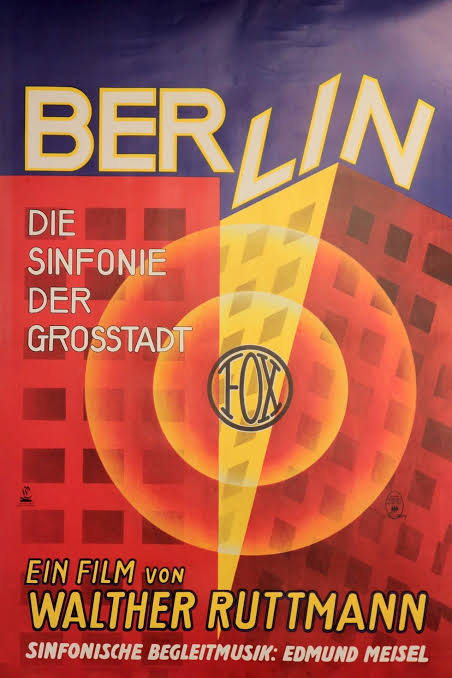

In recently viewing the scoring screener of Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927) that was provided to me by MoMA, I had a unique opportunity. I was able to watch MoMA’s brand-new restoration, which was mute, while also hearing the film’s original score recorded by an orchestra.

For the film’s premiere in 1927, Edmund Meisel composed an orchestral score for it. Meisel’s name may be familiar to you because of his score for Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin. I logged on to my library’s website and searched for the score, and discovered that there was an item that listed having a “web resource” with a link. Clicking it took me to a piece of the Naxos label website, which allowed me to stream anything in that label’s collection through my library.

Lo and behold, there is a CD of the Meisel’s original score for Berlin: Symphony of a Great City, and the timings on each of its tracks, one for each of the film’s five acts, almost exactly matches the acts’ timings on MoMA’s new digital restoration, which runs at 20 fps. I was able to watch the film with the Meisel score (basically) synced to it by having two windows open – one for the screener and one for the music – running the two in tandem “Vitaphone-style”.

The Meisel score may very well have been the cutting-edge of symphonic music in the late 1920s in Germany, but it does not hold up well as far as what most people today expect from a film score. The music does not have any themes or melodies – none that I can readily recognize, anyway – and is a bit on the dissonant side throughout. It also tends to reflect or mirror what we’re watching, as opposed to supporting the emotion of any of the scenes, at least the way I understand the process to be.

When there is a train hurtling along tracks to or through the city, the music gets more dissonant and bombastic. When we see children, we are treated to strings and winds in a higher register. When construction equipment is banging against each other we hear clangs, and when there is a policeman directing traffic, we hear a whistle. The music’s dissonance and lack of pleasant-to-our-ears-sounding melodies for most of the score does not exactly line up with the film’s sub-title Symphony of a Great City either, nor does it support or underscore the beauty shown in the film’s cinematography.

A quick trip through the Media History Digital Library via its Lantern search engine only turns up a few articles, but no ads or reviews from 1928. All of the articles I found are from 1929-30 issues of amateur movie maker magazines. Was Berlin: Symphony of a Great Metropolis (one of the ways the title has been translated from German) shown widely in the US? IMDb lists its USA release year as 1928. I sincerely doubt that the Meisel score was heard anywhere in the US ever, or that a cue sheet was published for it for screenings that did happen here.

And so I feel a little less weird about creating my own score for the film when I perform for it on Wednesday, July 30, at MoMA, knowing that an “original score” for the film exists. The music is probably available somewhere, although I’m sure that involves a costly license, and performing it would involve several days of my wood-shedding the music.

I’m also more interested in helping our audience on a summer weekday evening – who’ll be sitting outdoors in MoMA’s Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden – have a good time. Following the Meisel score’s, dark and semi-oppressive feel may not be the right fit either.

I’m going to watch the film one more time, without the Meisel score, so I can hear my own ideas and to see if I can find an internal dramatic structure and ebb-and-flow to the film and its individual 5 acts that make up the day-in-the-life of Berlin depicted in the film.

We’ll see what I wind up playing at the show when it happens on Weds July 30. Tickets are now on sale through MoMA’s website.