There’s a moment in Vidor’s The Crowd that I handle in a similar way to a moment toward the end of Hands Up! with Raymond Griffith. The effect I like to think what I’ve done on the Vidor had is what prompted me to use it on the Griffith. It’s something I learned from Lee Erwin right when I started playing for films.

I don’t own a working time machine (flux capacitor on back-order), so I’m trusting my memory from my college days, but the chronology fits. I’d started playing for films in the fall of 1981 — 35 years ago — at NYU. I’d visited Lee Erwin at the Carnegie Hall Cinema, where he was house organist, and hung out with him, asking him lots of questions and absorbing as much as I could. Lee had played for films in the 1920s and was still at it.

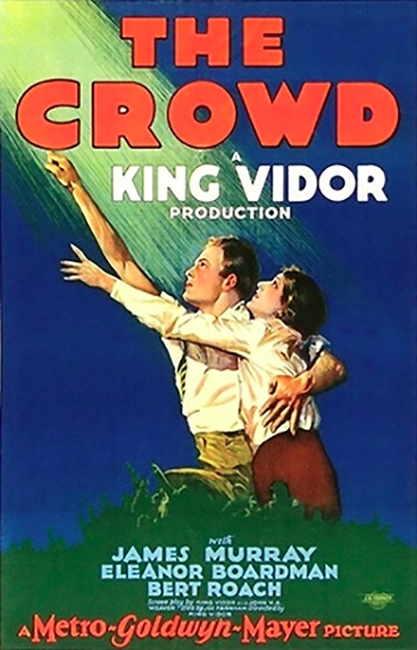

One of the last films of the fall semester course taught by Robert Sklar was Vidor’s The Crowd. There’s a moment about halfway through where there’s a tragic event (I won’t spoil it for you here) where the main character, Johnny Sims, is trying to keep everything and everyone in the flat he and his family live in as quiet as possible. The film crosscuts to a variety of loud noises happening outside and back to Johnny, who runs outside to try and quite the fire engines et al disturbing the peace he’s trying to maintain at home.

What was I to do? Play the quiet and tragedy and then switch to loud clanging music to match the outside world and back and forth? This would certainly take a bit of rehearsing to get the timing right, even if I was to attempt it. I don’t remember if I talked to Lee about this particular scene, but I can’t imagine I didn’t given how I wound up playing for it…and still do.

Lee’s rule or advice was to pick one “side” and stay with it instead of trying to hop back and forth. Coming to film accompaniment from being a filmmaker and silent film fan, this made sense to me aesthetically. It helps anchor the audience to the internal, emotional reaction of the character we’re paying attention to. After all, the cutaways are actually there as visual cues to us as to what’s occurring in the internal narrative of the character.

What I do for the sequence in The Crowd is stay on Johnny Sims’ devastation and his urgency to quell the cacophony of the outside world in his panicked desperation to aid his family in this time of sudden tragedy. So that the audience sees the shots of fire engines and newsboys yelling et al through Sims’ perspective. Does it work? I think it does.

I play with it a little every time I accompany the film — as I did recently at a show at Bard College — finding a way to blend the two visually disparate elements without looking like I wasn’t watching the film. I recorded my score at the Bard show and ideally will include an excerpt from this sequence on my next podcast episode.

There’s a moment at the end of Raymond Griffith’s brilliant comedy feature Hands Up! where Griffith stands, frozen in place, while everyone around him is cheering with unbridled jubilation. An event has just been announced that is incredibly fantastic news to everyone. To everyone, that is, except Griffith, for whom everything he’s done in the five reels leading up to this moment, the game he’s been trying to win, is now irrelevant. I usually do the same thing, holding musically on the moment Griffith is experiencing, while we cut back and forth from the medium shot of him just standing there taking it all in to crowd shots of cheering and dancing about.

This technique doesn’t apply to all situations, of course. There are some sequences in silent films that give equal screen time or dramatic weight to the pieces we’re cutting back and forth to, as opposed to having one side be cutaways to aid the expression of our main character. Handling this type of situation is the subject for another post.