There’s another by-product of my doing a live score for the 1931 Dracula, one that I think is a little more important than the issue of whether or not the music should be added or whether it works. It ties in with one of my main interests in silent film.

When my daughter was younger, I’d get up early and make sure she was up, fed, and off to school in the morning. Once she was out the door, I’d turn on TCM and have some more coffee. Quite often, it seemed to me anyway, what was programmed at that time were films from the early 30s. I’d watch them sometimes, fascinated by the different studios and directors’ attempts at finding their way with talking pictures. Not as exhaustive a study as in the book After the Silents by Michael Slowik, but I definitely got the impression that the stereotype of early sound film being stagey and creaky and often slow-paced was not really true.

There was a range of techniques. There is camera movement, there is effective cutting, there is creative use of sound, there is occasionally inventive use of bits of underscore even if it is instrumentals of pop tunes coming over a radio. There is also a lack of all this.

Like I said, there’s a range…but it’s a range. It’s not all photographed stage plays.

The creakiness comes from a combination of the slower and more deliberately paced or spoken dialog, and from the lack of musical underscore. The performance slowness is a mix. There are silent era actors who were still used to adjusting their timing for the slightly undercranked camera speeds. Also, it’s been explained to me that there was a need to accommodate the current microphone technology and the amplification in movie theaters, cinemas whose acoustics were fine for silents but not ideal for the newly installed loudspeakers.

A lot of early sound film is better than you’d think, but certainly musical underscore’s absence hinders these pictures. It’s one of the things you hear about the 1931 Dracula, a film that you’d think would be shown more often giving its iconic status.

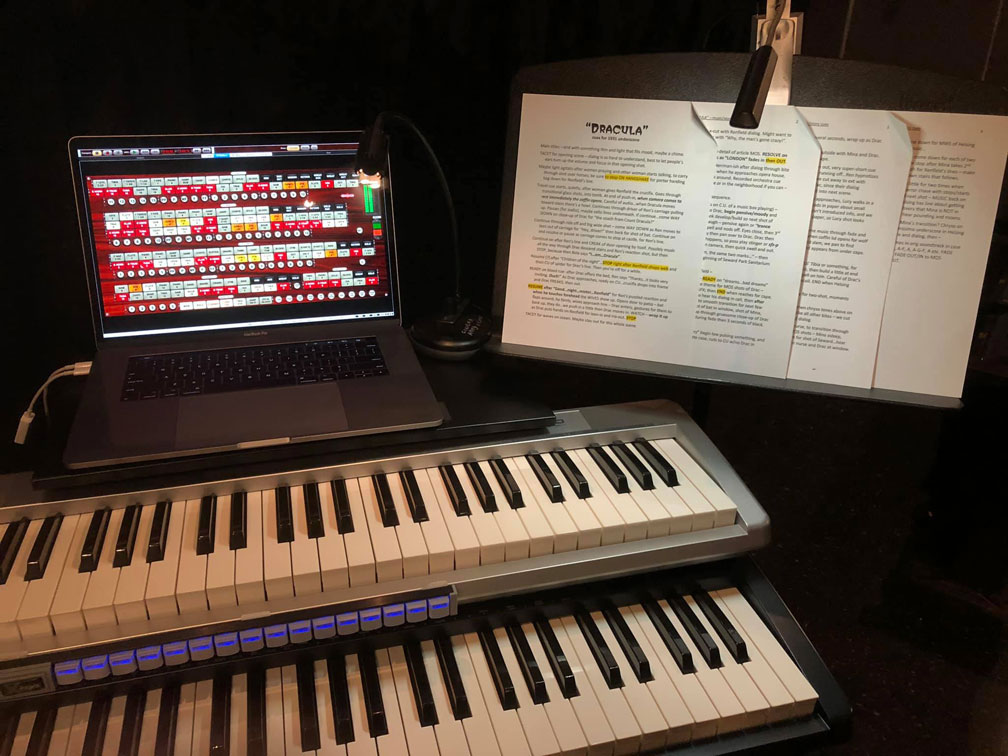

My trying out the live underscore idea is more than a musical experiment (which really works, as it turns out). It’s made the film even more enjoyable and, so far, has meant that it’s gotten screened a little more. The idea may sound gimmicky on the surface, but the 1931 Dracula deserves to be shown theatrically more than it is. I’m really careful about my transitions starting in to the different cues, and try my best to be unobtrusive and true to what you might expect from a 1930s film score.

Plus, the interesting thing about the nearly-MOS sequences in the Todd Browning Dracula is that cinematically they employ the language of silent film. They’re well shot, well composed, and each shot gives us new information. We’re not sitting there watching a scene from a play where no one is talking. In some ways it’s almost as if the film is a part-talkie in reverse — a talking pictures with some silent sequences.

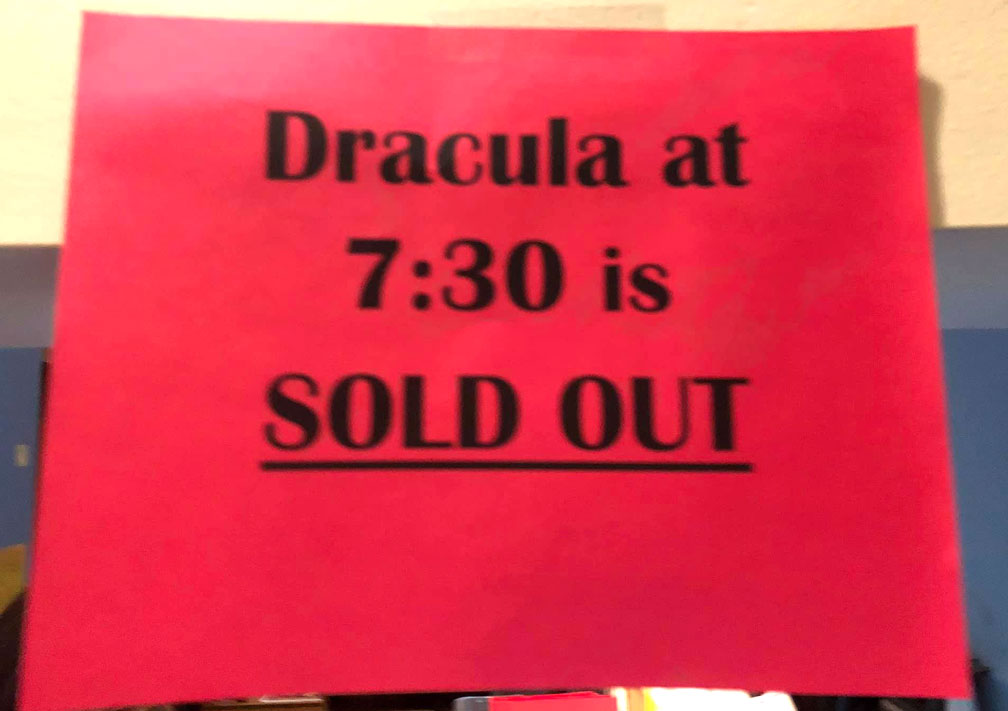

The sold-out show I did last night at the Cinema Arts Centre proved there’s an audience for this film. If nothing else, I can tell you the shows I’ve done in the last two years are three more showings of the Browning-Lugosi Dracula than there were going to be. It’s not like the film had been programmed and then we decided to add the live music.

Helping a great film get shown more, and be enjoyed by fans in a movie theater — that’s audience preservation.