As a fan and proponent of silent films, I’ve enjoyed seeing that every year at Halloween time, more and more shows of silent films are happening. It’s occurred to me that this means there are a lot of musicians accompanying a silent film for the first time and may be wondering how to go about it. If that’s you, I’d like to lay out a few basics and rules that may help you out, based on my 40 years accompanying silent films.

Some of this will be incredibly obvious to you, and some of it may be news. I’m trying to cover the bases for everyone here.

This blog post is also available as episode 30 of my podcast, which you can listen to here.

What are the Halloween Silent Movies That People Show?

There are some usual suspects that get shown every year on Halloween: Nosferatu (1922), Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1920), The Phantom of the Opera (1925), and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920). I’m sure I’m forgetting a couple favorites. A less-famous but equally macabre or spooky film is The Cat and the Canary (1928), one of the original spooky old house where the family of a dead millionaire has been summoned for the reading of a will and people keep disappearing. There are also other Lon Chaney films besides “Phantom” to consider. Two that get shown are The Penalty (1920) and The Unknown (1927). There are other films in the canon to choose from, I’m sure.

Aren’t All Silent Films In The Public Domain?

Nope. This topic is a bit complicated as far as what is and what isn’t p.d., and the companies who have produced the DVD or Blu-ray you may be choosing to show at your program probably would appreciating your licensing the show from them. Even if it is a film that is in the public domain, they’ve either paid for or licensed the restoration of the film on the disc. Silent movies are not supposed to look scratchy, schmeary, and jittery, and there are a few companies like KinoLorber, Flicker Alley and the Warner Archive Collection that have released quality editions of the films you want to do. It’s a good idea to license your show. I’d also encourage you not to just download or rip something from YouTube. Your results may vary, and how you choose to proceed is up to you.

How Should I Prepare?

This is up to you, as far as what works best for you and what your anxiety-nervousness level may be for a performance. You’ll definitely want to pre-screen the film at least once and take story notes, including timings so you’ll know how much music you’ll need to find for a given scene. You may want to write things down that will remind you of an action to look for that happens just before some big action, scare moment, or mood shift. Having this “cue sheet” on the music rack can help you stay on top of and ahead of what’s happening onscreen.

Rehearsing with the film projected as opposed to on a TV set is something I’d recommend. It’s not always possible, but the larger projected image that you’re looking up at will more closely match the emotional reaction you’ll have during the actual show.

What Kind of Music Should (and Shouldn’t) I Play?

Your scoring should take the film seriously, underscoring the drama and emotions of the scene. It should not comment on or make fun of the film. The films and the music for them were taken seriously in the 1910s and 1920s, and should be by you for a contemporary audience. Try and match the feel of the piece of music to the internal drama of the characters, as opposed to what I think of as “Peter and the Wolf” scoring, i.e. having a theme for each character and playing it every time they show up onscreen.

Someone emailed me recently about a scoring project for a silent film-style video, and used a few adjectives to describe the style of silent movie music they had in mind. One of the words they used was “corny”. I don’t think that’s what they were going for and, as it turned out in the following email exchange, it wasn’t. The word “corny” is like a lot of other things most people associate with silent movies — women tied to train tracks, dangling off a cliff, people engaged custard pie fights — comes from a stereotype that is not actually rooted in the silent era.

Silent movies were ridiculed and derided as a quaint antique of a bygone era almost immediately after talking pictures took over. The hokey narration or title cards referring to onscreen characters as the villain, hero and damsel in distress, the title cards with curlicue borders (almost never used in silents), over-the-top ham acting people think of is rooted in stage melodrama that preceded the silents, and was for some reason perpetuated as silent film fact in spoofs of silent movies ever since the 1930s.

The rinky-tink upright piano sound and cornball music cues that people sometimes think are “What You Play For Silent Movies” is another stereotype that’s been perpetuated by spoofs and recreations of silents from TV going back to the 1950s. But it’s not typical of appropriate silent film music.

The “don’ts and be carefuls” of silent film accompaniment are pretty simple.

Avoid playing recognizable music if you can help it. I realize you may not have the ability to improvise, or may be daunted by the idea of improvising a 90 minute film score. The thing to remember is that your audience may already have their own associations with with a familiar piece, whether it’s “The Ride of the Valkyries” or “Handel’s Messiah” and your use of that piece will trigger their association regardless of what yours is. Using stereotypical or over-used “mysterioso” music like “In the Hall of the Mountain King” or the beaten-to-death “Misterioso Pizzicato” should also be avoided.

Also, the use of quoting a familiar piece of music is seen today as wryly ironic, and is a cue for the viewer to not take what they’re watching seriously. Try to find music from the classical repertoire that is at least a bit more unknown than things you hear in commercials or ringtones.

Don’t overuse a piece of music or a tune you’ve chosen as a theme. 3 or 4 times during a film should be sufficient. Otherwise you run the risk of the audience being pulled out of the experience and thinking “oh, here’s that music again”. I know, I know, the scores for Harry Potter and Star Wars movies employ this, but maybe don’t do it for your silent film score.

Don’t do what I call “song title puns”, meaning playing a popular song from the 20s or any era whose title matches up with something happening onscreen. Someone attended a show at a church of “Phantom of the Opera” a few years ago and told me that in the scene where the Phantom descends into the water in the catacombs under the Paris Opera House, the organist played “Under the Sea” from “The Little Mermaid”. It got a big laugh. That’s not what that moment in the film is about, and it just calls attention to the musician in the theatre.

I’d also recommend staying away from sound effects — a downward glissando smear when someone falls and then smacking a cluster of bass notes when they hit the ground. Doing this just calls attention to the musician and pulls focus from the film. Also, it’s really not all that easy to synch up and if you miss the cue then the audience not only more aware of the musician they’re also aware that you’ve missed the “hit”.

You also don’t need to play a ton of music and have a constant, busy wash of notes. You can hold chords, play simpler lines, etc. The audience is trying to watch a movie, and you’re there to help them decode what may need help decoding…but no one’s there for a concert. The busier the music is, the more the audience has to focus their brain on the drama and emotions of the film.

Where Do I Find Enough Suitable Music for a Silent Movie Score?

I’ll make finding music a little easier for you. There’s a great resource to find and download PDFs of mood music composed and published in the silent film era. It’s called the Silent Film Sound and Music Archive, or SFSMA. In the ‘10s and ‘20s, hundreds and hundreds of pieces of music were composed and published for silent film accompaniment. They resemble classical music, except that instead of shifting mood every 16 or 32 bars, they sustain a particular mood for 3-4 minutes so you have enough music for a particular sequence. During the silent era, every movie theatre had a music library of these mood cues as well as classical music and more, for the solo accompanist or orchestra conductor to draw on and compile their own score or to mix in with their improvisations.

SFSMA has several hundred of these pieces, for piano and for small or large orchestra, all downloadable in PDF form.

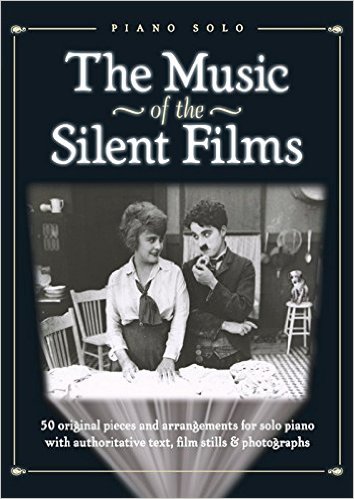

It is a lot to sift through, though, and I’ll make that task even easier, although it may cost you around 30 bucks. In 2015 MusicSales published a sheet music book that I compiled and edited called “The Music of the Silent Films”. The book contains 50 pieces of vintage “Photoplay” music for silent films, which I’ve organized by mood. The book is a good “starter kit” for silent film scoring, and includes a section with history on silent film music, biographies of the folks who composed the mood cues, and some basics on silent film scoring. It’s available worldwide, on Amazon and other sheet music websites.

It’s Not About You. Honest!

It’s true. It’s a weird duality to experience, as a performer and composer/compiler of a 90-minute film score, that people are really there to see the movie, and not necessarily to hear you play music. Especially when everyone involved has been dead at least 60 years, and you’re the one who can take a bow at the end of the film. My mentor in silent film accompaniment, Lee Erwin (1908-2000), who was an movie organist in the 1920s, told me the best compliment you can hear from someone after a show is “I forgot you were playing”.

Most of all, have fun, and I hope your “spooky silents” show at the end of October goes really well. If the organizers want to do it again next year — or sooner! — then you’ve done your job well. If you want to hear more about the subtleties and techniques of silent film accompaniment, check out my Silent Film Music podcast on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify, GooglePlay Music or Overcast.

If you have any questions about any of this, feel free to post a comment, email me or send a Tweet.

Thanks.

Ben Model

silent film accompanist-historian