Last week, I had another one of those film accompanist experiences where a spoken introduction helped shape the way I played for the film. There is currently a major gallery exhibition at the MoMA honoring the work of artist Joan Jonas. In conjunction with this exhibition, the film department has organized one of their “Carte Blanche” film series to tie in with the galleries, in which Jonas has selected several films to be screened that are favorites of hers. The series’ opening night selection was the silent film, A Story of Floating Weeds (1934), directed by Yasujiro Ozu.

I’ve mentioned on my Silent Film Music Podcast a number of times that I’ve found that staying open to suggestions and impulses before and even during a live accompaniment helps and can give me clues that I hadn’t thought of or considered in any preparation I’d done to accompany the film.

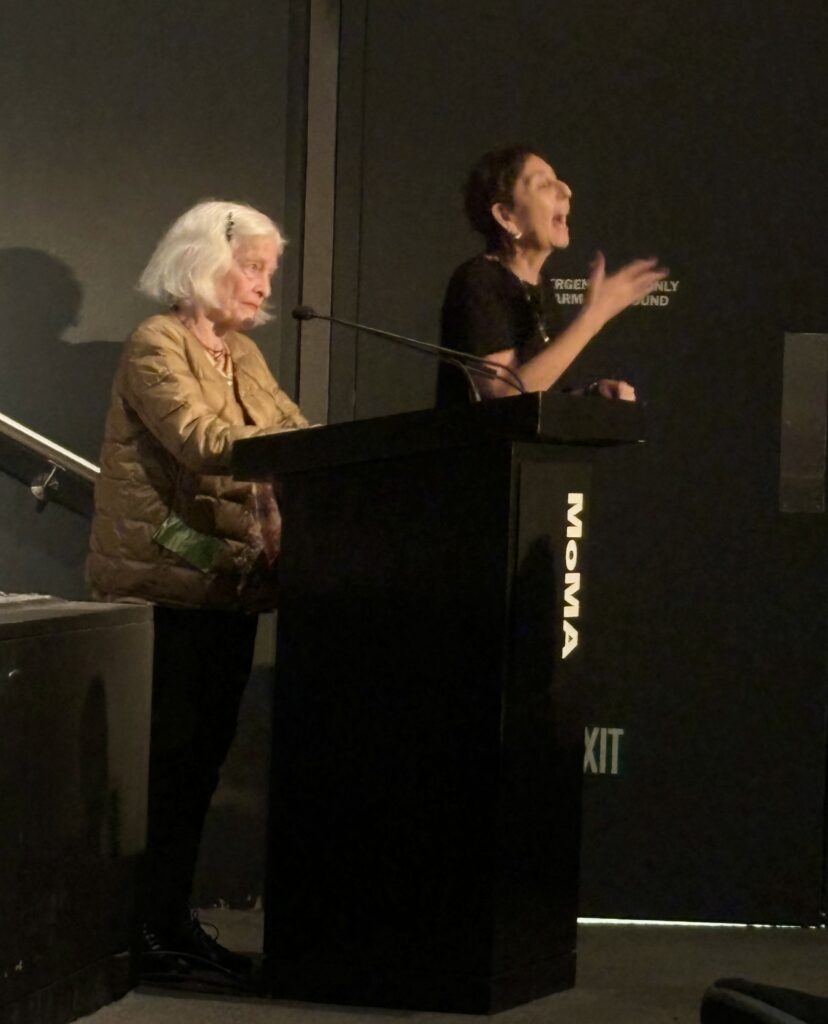

After MoMA Department of Film curator Joshua Siegel gave a brief introduction, Joan Jonas spoke briefly about her interests in and passion for cinema, and the film’s chosen for the series. She then mentioned that she had become aware of how she’d noticed that now views films more in terms of plot and character than she used to, and that she had formerly watched film more visually. In her thumbnail introduction to the Ozu film, she mentioned something that resonated with me – and which I think I may have read somewhere, but which was good to be reminded about. Jonas talked about how Ozu, at least in his silent films, had a practice of separating some of the scenes with moments of stillness.

When Joan Jonas mentioned this, a small light bulb went off over my head, and I thought this would be something I could try to connect with and support musically, as a way of partnering with the director’s style and rhythm.

A rule of silent cinema’s storytelling language that I have observed is that there is no wasted screen time in silent film. Every shot is on screen to bring us some information of some sort, to continue to engage us in the flow of the story. Rather than treat these moments of stillness, as they would occur in the film as moments that hold up the flow of the film’s forward motion I would support Ozu’s use of these shots as sort of a narrative “cleansing breath” between scenes as the film proceeded. While accompanying the film, I noticed these moments that would come up where Ozu would cut to one or two shots of objects in a room where the scene had been happening, etc. I found ways to do the same, musically. I didn’t take my hands off the keys and stop playing, but I played much, much less before launching in to the film’s next sequence.

This is one of the advantages of improvising a film score as opposed to playing a locked, written-out score. No matter how much time I may have spent ahead of time on any film, watching the film, taking notes, and jotting down musical ideas, someone may say something in their introduction that will give me an insight into the director’s vision that will inspire me to adjust my plans and to better support the film for the audience.

A Story of Floating Weeds (1934) was screened in a 35mm print that had been made for the 2003 Ozu centennial, which MoMA got from Janus Films.